What I learned from building autonomous model race cars for a year

I was part of a university project group that develops autonomous model race cars. We are a group of twelve students working on the project in part time for year.

We were provided with a car that meets the requirements for the F1/10th competition. Even though competing in F1/10th was not our goal, we kept the rules for the competition in mind. We focussed mostly on trying different driving algorithms, which I'll explain below. The software we developed is available on Github.

This post is about what we did and what insights I gained from this work.

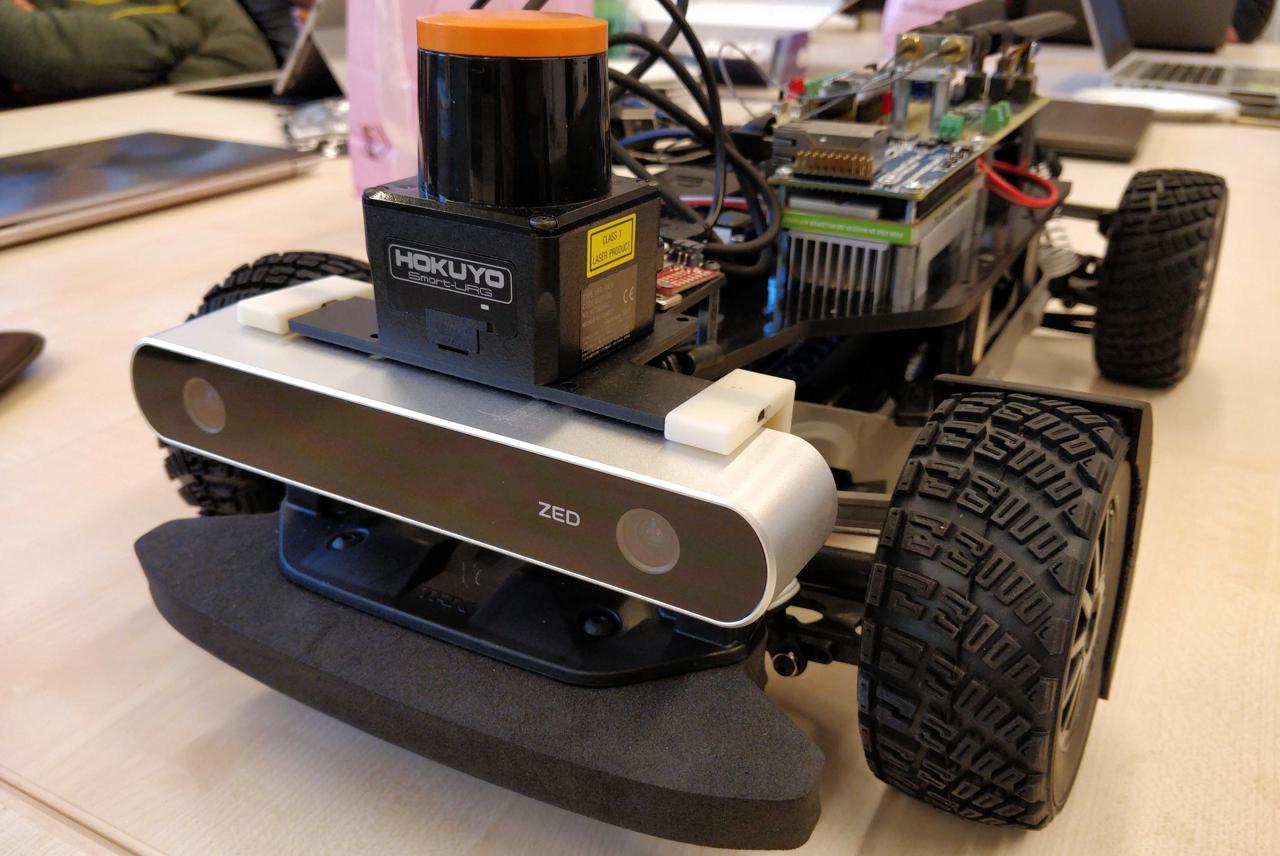

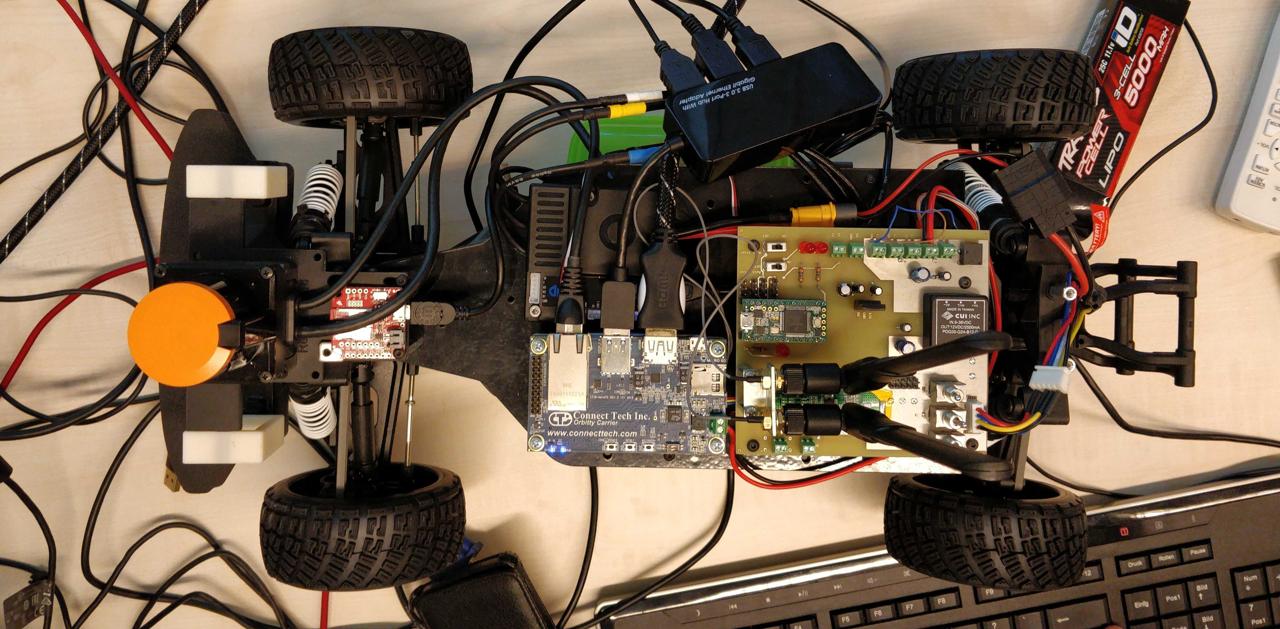

Hardware

Our car is a regular 1/10 scale RC car where the the RC receiver is replaced with a computer. The car is based on a Traxxas Ford Fiesta ST Rally. The computer is an Nvidia Jetson TX2. The car is equipped with a LIDAR scanner with a resolution of 1 ✕ 1080, an IMU and a stereo camera. We ended up not using the stereo camera.

ROS

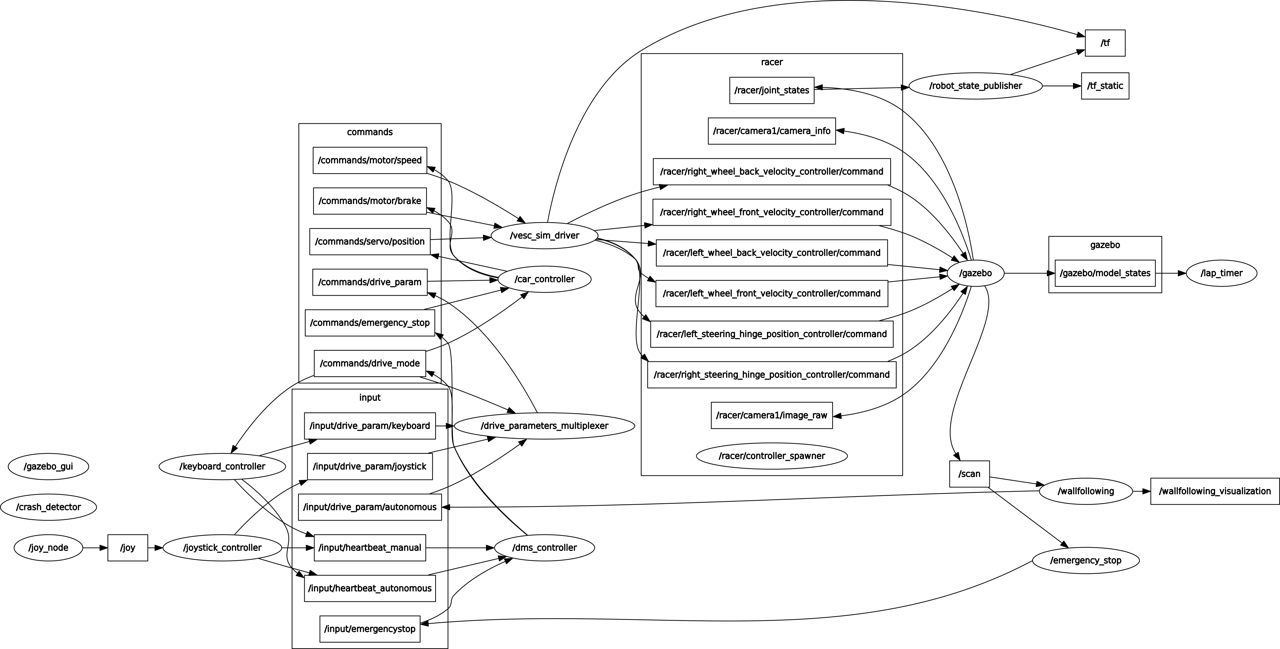

Our software stack is based on ROS and Gazebo. We used ROS and Gazebo because it is the standard for academic robotics projects. Most online materials assume that your project uses on ROS.

ROS is a robotics framework that facilitates communication between robot compontents such as sensors and actors. All the hardware components we use have ROS nodes that publish or subscribe to data in a standardized way. ROS provides a rich ecosystem of software. For all kinds of robot parts and control problems there are ROS nodes available. You can get pretty far by just tying together existing ROS packages. ROS nodes can be written in C++ and Python 2.7 and since each node is its own process, both languages can be used at the same time.

A ROS architecture is built like a distributed system with nodes that subscribe and publish to topics. This is the case even if everything runs on a single computer, like with our project. This creates some overhead. Using ROS means that you'll write lots of configuration files, package definition files, launch files, robot description files that all reference each other. With Gazebo, you'll also need mesh description XML files and world definition files. However, I think that using ROS is worth it for ecosystem of existing ROS modules.

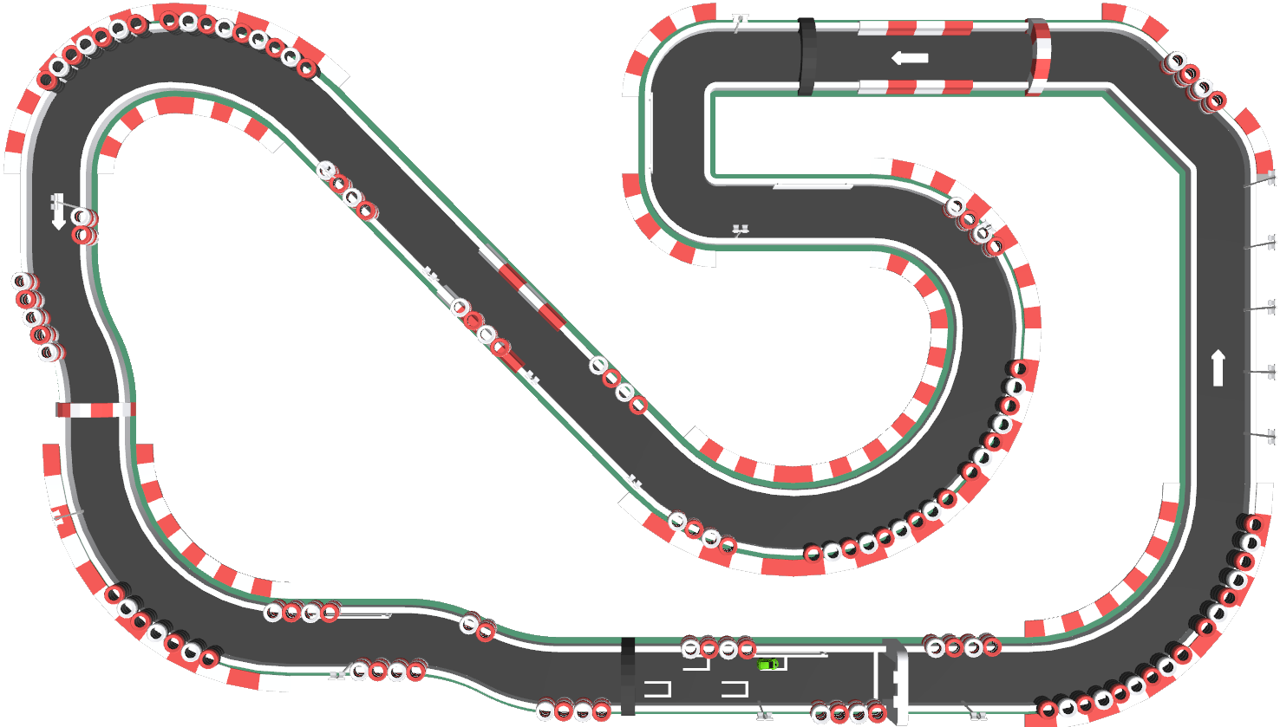

Gazebo

We use Gazebo as a simulation environment. Our robot car can drive in the real world and in the Gazebo simulation using the same software. Having this simulation turned out to be extremely useful. Since we mostly used the Lidar, the simulated track is designed with walls enclosing the track. The visual appearance and realism was less important for our use case.

What follows next is my rant about Gazebo. Gazebo is bad software in every way. It is poorly documented, buggy and misses important features. For example, about 20% of the time, Gazebo doesn't launch at all and crashes instead. In the video above, you can see that the car receives shadows, but the track doesn't. See how the car isn't shiny? That's because Gazebo's lighting model doesn't support metalicity. Getting it to render the scene this decent was super difficult, it would be trivial to get way better looks in an engine like Unity. These are just a few out of many problems we had with Gazebo. Seemingly trivial things are unneccesarily difficult.

My takeaway is: Avoid using Gazebo if at all possible. Use a game engine instead. Getting a working game engine to simulate a robotics scenario is way easier than getting Gazebo to do what it's supposed to do. For example, there is a project to let ROS communicate with the Unity engine. This is what you should use instead, it will save you a lot of headaches. There are some features in Gazebo specific to robot simulation that a game engine doesn't provide, such as a headless mode.

Now for the interesting part, the autonomous driving algorithms. All algorithms use only LIDAR and IMU data. We didn't use the camera.

SLAM

SLAM stands for simultaneous localization and mapping. It is the concept that the robot determines its own position in an unknown environment based on a map that it creates while exploring the enviroment. For autonomous racing, this means that the car generates a map of the racetrack and can then calculate and follow an ideal racing path using that map and its position.

Since we use ROS, we can use lots of existing SLAM implementations that are built specifically for ROS. In addition, ROS offers the navigation stack, which has implementations for path planning and execution. But working with SLAM in practice turned out to be difficult. The existing SLAM algorithms are mostly designed for slow robots and stop working at higher speeds. This makes them unsuitable for racing. But seeing the map generate looks pretty cool!

Wallfollowing

Wallfollowing is what we call our greedy driving algorithm. It has no concept of the track or the ideal path. It only considers the part of the track that the LIDAR can see from the current position of the car.

Our approach is to separate the laser sample points (shown in red) into a left and a right wall and fit two circles into them. The algorithm calculates a predicted position of the car (in the center of the video) and a desired position (in the center of the track). The difference between them (shown in orange) is used as the error for a PID controller, which controlls the steering. To control throttle, we calculate multiple maximum speeds based on the PID error, the curviness of the track and the distance towards the next obstacle (shown in yellow). Out of these maximum speeds, we apply the smallest one. This allows us to slow down in curves, cut corners, etc.

Teams competing in the F1/10 competition typically use an approach like this. The wallfollowing approach provided the best lap times in our tests.

The videos for Gazebo and for SLAM above show the car being controlled by the Wallfollowing algorithm. Here is a video of the physical car driving with it:

Reinforcement Learning

One of the methods of autonous driving we tried during this project group was reinforcement learning. It is an area of machine learning where an agent, in our case a car, learns to select actions given a state to optimize a reward function. In particular, we used deep reinforcement learning, where the function that selects an action given a state is a neural network, instead of a lookup table.

In our case, the state vector was a downscaled version of the Lidar scan. That means, each element of the vector contains the measured distance for a fixed direction. We also experimented with other state information, such as velocity and throttle, but this didn't bring any improvement. In reinforcement learning, the actions are discrete, meaning that the agent selects an action out of a finite set, instead of providing numbers for throttle and steering. In the simplest example, we used a fixed velocity and two actions for steering left and right. Straight driving would be achieved by oscilating between left and right. We also tried more granular action sets, but this increases the difficulty of the learning task. The neural network has one input neuron for each element of the state vector and one output neuron for each action. It predicts a Q value for each action and the car will perform the action with the highest Q value. During training however, sometimes random actions are taken instead, according an epsilon-greedy policy (exploration vs. exploitation). For the reward function, it would be possible to use a reward of 1 for each step. There is an implicit reward for not crashing as this leads to longer episodes and the reward is accumulated over the episode. But it will learn to stay in the center faster if we give it higher rewards for driving close to the center of the track and lower rewards for driving close to the walls. In addition, we reward high speed.

We tested Q-Learning and Policy Gradient. Both took hours to learn to drive in the center, but eventually did so decently. Overall, policy gradient worked better than Q-learning. But both were unreliable in the simulation and didn't translate well from simulation to reality. I think that we could achieve significantly better results if we had more time.

This is a video of the car driving in our simulation with policy gradient:

Evolutionary Algorithm

For the evolutionary algorithm, we took the neural networks from our reinforcement learning approach and learned the network parameters with an evolutionary algorithm. Instead of using a set of actions, we let two output neurons control throttle and steering directly. We started with random weights and randomly changed them while measuring the performance of the car in the simulation.

Surprisingly, this worked about as well as reinforcement learning, but was easier to implement and took less time to train. However, like reinforcement learning, it did not perform as well as our wallfollowing algorithm.

Outlook

Since our goal was not primarily to participate in the official competition, we investigated sevaral methods of autonomous driving. The least fancy one, our greedy wallfollowing algorithm, turned out to be the fastest. All of the driving methods could probably be improved with more time. There is a follow-up project group that continues to work with our code base. It looks like they are even working on moving away from Gazebo.